Like many in Seattle’s downtown business community, Ali Ghambari, owner of Cherry Street Coffee House, has little idea how to plan for a post-pandemic economic recovery.

Before COVID-19, Ghambari’s downtown locations — he had 11, but just four are still open — relied heavily on office workers and tourists. But Ghambari doesn’t know when vaccines will allow tourism to return. He doesn’t know when big downtown employers will reopen their offices, or how quickly workers will actually give up their home offices and start coming back downtown.

And even when downtown Seattle starts to refill, Ghambari worries that his own recovery could be blunted by problems with homelessness and street crime that were already serious before COVID-19 — and are now so disturbing that he had to install buzz-in door security at his Pioneer Square store or “my employees would have quit on me.”

“Realistically,” says Ghambari, “we don’t know what the new normal is going to look like.”

The stakes are enormous. Since the first stay-at-home orders last spring, 163 downtown Seattle restaurants, shops and other street-level business locations have permanently closed, according to the Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) — and anecdotally, many more may be at risk of shutting down.

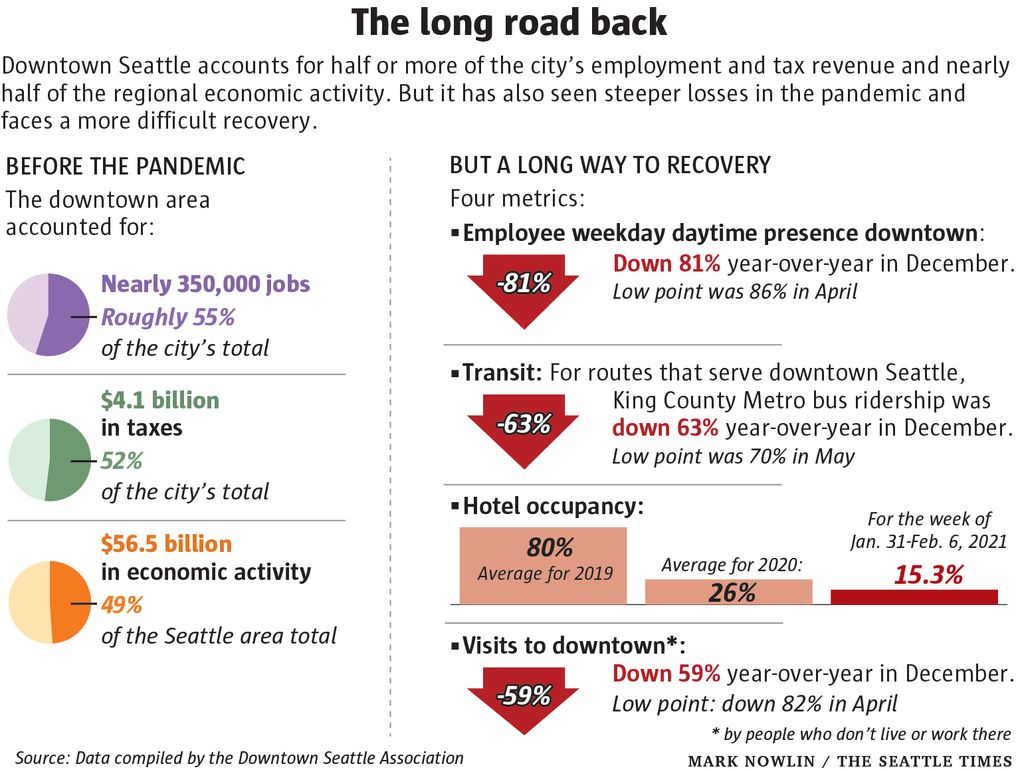

More broadly, before COVID-19, downtown Seattle was the city’s economic engine. It accounted for more than half the city’s jobs and tax revenue. Its restaurants, nightclubs, retailers, concert halls, stadiums and other attractions, like Pike Place Market, were magnets for tourists as well as the workers who turned Seattle into a “superstar” city.

But almost overnight, those strengths became weaknesses as COVID-19 eliminated the dense social and commercial interactions that make big-city urban cores so economically dominant. Compared to many other Seattle neighborhoods — and, to a lesser extent, rival downtowns in Tacoma and Bellevue — Seattle’s downtown often seems like a ghost town.

As of December, just one in five employees who had previously worked in downtown Seattle was back in their employers’ workplace, according to cellphone location data from Placer.ai. Downtown hotels were at 15% occupancy as of early February. The massive Washington State Convention Center is largely silent and many storefronts are still boarded up, some dating back to the vandalism that accompanied some of last year’s demonstrations.

Downtown boosters say Seattle will bounce back. Its broader economy remains strong and its tech sector is so hot that even during the pandemic it pulled in 2.2 workers for every one who left, according to data from LinkedIn.

The city of Seattle, meanwhile, is launching a “Downtown Revitalization Working Group”focused on an accelerated vaccine rollout, supporting smaller, disadvantaged businesses, and addressing “the root causes of homelessness,” among other issues, says Mayor Jenny Durkan. A major effort to clean up graffiti and un-board storefronts is also underway.

But even downtown’s most ardent boosters know that a full recovery will take years — and could be derailed by pandemic-related problems like a vaccine delay or a surge in COVID-19 cases. Office workers and shoppers could be kept away by health anxieties over public transit — or fears over crime in the downtown area. The smashed windows at Nordstrom’s downtown store last Sunday were only the latest reminders of security concerns for an area where police recorded more cases of homicide, arson, burglary and vehicle theft in 2020 than in 2019 or 2018. If local governments can’t confront downtown’s homelessness, drug abuse and street crime problems, Scholes says, “talk of recovery is hollow.”

And beneath these pragmatic concerns is another recognition: that COVID-19 has weakened the pre-pandemic arguments for coming downtown in the first place, thanks in part to the success of remote work, online shopping, and other pandemic-related disruptions and developments.

Vacancy rates are soaring downtown for office space. One in every 10 downtown apartment units was empty at the end of 2020, in part as some downtown residents used the shift to remote work to find cheaper or roomier digs elsewhere. By DSA estimates, downtown’s residential population fell by 5,000, to 84,000, during the pandemic.

“We’re going to have challenges we didn’t have before,” Durkan concedes.

Those differences make it difficult to predict what a post-COVID-19 downtown looks like or how to prepare for it, says Margaret O’Mara, a University of Washington historian who has written extensively about tech hubs like Seattle. “It’s all in flux right now, and it is kind of impossible to plan,” she adds.

More questions than answers

Those uncertainties run the gamut for downtown businesses. Downtown retailers, for example, have no way of knowing how many of the customers they lost during the pandemic to online shopping or to regional malls will come back downtown.

And that grim forecast came before Canadian authorities recently extended the ban on large cruise ships and effectively canceled Seattle’s cruise season for a second year. “We’re kind of up a river without a paddle,” says Jess Hibbard, a longtime vendor at Pike Place Market who was helping a friend sell T-shirts last week, and who says cruise ship passengers usually account for almost all of their business.

But the greater uncertainty, arguably, centers on the future of work downtown.

Before the pandemic, according to DSA estimate, there were around 348,000 downtown workers, most of them commuters, whose spending on everything from coffee and lunches to happy hours and sporting events was the lifeblood for many downtown businesses. (DSA estimates 20,000 of those downtown jobs were lost in the pandemic.)

But it’s not like flipping a switch, business owners say.

Steve Hooper Jr., president of Ethan Stowell Restaurants, plans to reopen four of the company’s six downtown eateries (two are already open) shortly before Amazon and other big downtown employers have said they’ll bring back workers, possibly in early summer.

But Hooper knows it’s a soft target: Even when public health officials give the OK, some employers are likely to bring workers back in stages. That leaves restaurateurs to guess when their respective downtown locations will hit a “tipping point” of enough foot traffic to justify reopening, Hooper says.

That uncertainty is one reason DSA has been lobbying downtown employers to go public with their back-to-office timelines. Employers may not be ready to “announce that they’re bringing everybody back by June,” says Scholes. “But can we get a few of them that say, ‘Yeah, we’re going to open up to 25%’? That starts to create some confidence and momentum.”

But results so far have been mixed. Some employers are reluctant to reveal their return timelines or plans.

Amazon, whose roughly 50,000 downtown Seattle employees are mostly working remotely, publicly has said only that its remote work policy will continue through June 30, 2021. A spokesperson declined to comment on how quickly employees might return after that.

Some big downtown employers are making clear they’ll have fewer workers in the office even after the pandemic.

Nordstrom plans to give up more than a third of its downtown office footprint, at least in part as it relies more on remote work. Dropbox and F5 also plan to sublease some of their downtown space in part because of more remote work.

Zillow, which had around 2,000 employees in downtown Seattle pre-pandemic, says 90% of its workers can work remotely at least part of the time after the pandemic.

Facebook, which has around half of its 5,000 local employees based in downtown Seattle, says it’s still developing a post-COVID work strategy but is likely to have a flexible model. To that point, many workers Facebook hired for Seattle-area positions during the pandemic were allowed to telecommute from up to four hours away from the city — and they’ll be able to keep doing that.

“When we do go back … it certainly will be at reduced capacity,” says spokesperson Tracy Clayton. “It won’t look like it did before.”

Smaller firms are also preparing for a smaller downtown presence. Over half (57%) of Seattle employers with 100 or fewer workers are considering permanent increases in the number of employees who work remotely, according to a survey by Commute Seattle.

Derrick Morton, CEO of Seattle gaming company FlowPlay, says more than half of his 61 workers will keep working from home. Though he expects to eventually resume FlowPlay’s pre-pandemic work model of three office days a week, the strategy ultimately will be shaped by employee sentiment and “how it’s working for everybody to be back, whatever that means.”

These shifts will affect not only how fast downtown recovers, but what downtown looks like post-COVID-19.

One obvious difference is that many firms will need less office space, at least in the near term.

Vera Whole Health may cut its 13,000-square-foot office footprint by perhaps a third, Schmid says. FlowPlay is considering subleasing half its 12,000-square-foot office on Western Avenue, says Morton.

It’s also a factor in the ballooning supply of downtown sublease office space, which jumped last quarter to 3.7 million square feet, or 4.7% of total inventory, from 3% a year earlier, according to Nicholas Carlsen, a research analyst in the Seattle office of Colliers. For comparison, during the Great Recession, the downtown sublease supply peaked at 2.5% of total inventory, Carlsen says.

The mix of businesses downtown could also change. Even before the pandemic, Hooper says, downtown Seattle was widely regarded as “overfed” with too many restaurants.

With the prospect of fewer workers downtown, Hooper expects fewer restaurateurs or other businesses to gamble the capital necessary to open or reopen downtown.

That in turn could change downtown’s social and cultural fabric.

Fewer downtown restaurants and shops, for example, will mean an even smaller contingent of entry-level workers in a downtown that was already tilting upscale.

It also could shift downtown’s street scene by changing who leases street-level retail spaces downtown, says Damian Sevilla, a vice president with the Seattle office of commercial real estate firm Kidder Mathews.

Whether such shifts would be permanent is hardly a settled question. Some employers, for example, say they’ll adjust their workplace models as they learn how remote work affects productivity and worker satisfaction longer term.

But other observers think COVID-19 already has permanently altered the relationship between work and workplace. After the pandemic, “there’s not going to be a default setting” that “you go to an office for five days” a week, says O’Mara.

That has been the pandemic lesson for mega-hubs like San Francisco and New York, which have seen a steady exodus of workers.

But it may also be an emerging reality in downtown Seattle — especially as employers compete for highly skilled workers who now prefer remote work, and don’t care that a company just opened up a brand new downtown campus. “None of that matters,” says Heather Redman, co-founder and managing partner of the Flying Fish Partners venture firm. “It’s all about where do the employees want to be and why.”

In Bellevue, the downtown office vacancy rate was around half of downtown Seattle’s and no buildings are boarded up, says Bellevue Downtown Association spokesperson Mason Luvera.

In downtown Tacoma, hotel occupancy is roughly twice as high as in downtown Seattle, and just five restaurants and retailers have shut down, says David Schroedel, executive director of the Downtown Tacoma Partnership and vice president of the Tacoma-Pierce County Chamber. The result is a downtown that, though quieter than it was in 2019, doesn’t look abandoned, adds chamber President Tom Pierson: “You don’t see the downtown today boarded up.”

Boosters of downtown Seattle insist that its slower recovery relative to some neighboring cities is due in part to its much greater size and density — features that complicate recovery, but also represent massive economic potential. As the vaccine allows resumption of dense social interactions, downtown’s variety of unique amenities will once again draw a disproportionate share of tourists, workers and residents.

But O’Mara says the pandemic has also forced a debate over how urban centers like Seattle will function in the future.

And in the meantime, adds FlowPlay’s Morton, “all we can do is sort of postulate today about what that might look like.”