News

The Seattle Times: Downtown Seattle considers a future with lots of tourists and few office workers

Posted on

This story was originally published in The Seattle Times on May 28, 2022.

Like many small businesses in downtown Seattle, the Pure Food Fish Market has had to adjust to an economy that’s still missing some of its pre-COVID-19 players.

While cruise passengers and other tourists are back to snapping up Pure Food’s fresh salmon and halibut and crab, the office workers who used to come to the Pike Place Market fish shop before heading home have been largely absent.

So much so that owners Carlee Hollenbeck and Isaac Behar have changed their schedule. Pure Food, which for 70 years stayed open till 6 p.m. for commuter sales, now closes at 5 because office workers “just aren’t showing up as often,” Hollenbeck says.

Pure Foods’ changing customer mix highlights an emerging, not entirely expected pattern in downtown Seattle’s pandemic recovery.

Early in the pandemic, some business leaders and experts imagined a downtown recovery led by returning office workers followed by a resurgence of tourism and other leisure seekers.

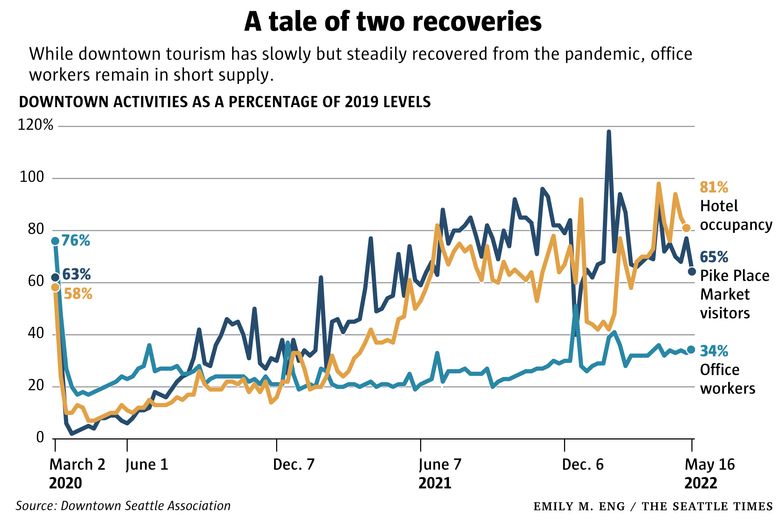

But to some degree, the reverse is happening. Even as the repatriation of office workers has stalled, downtown tourism and other leisure activities, including sporting events and live performance, has steadily come back, despite persistent stories of downtown crime and a recent uptick in COVID cases.

Visits to Pike Place Market between late March and early May averaged 74% of 2019 levels for the same period, according to cellphone location data from Placer.ai posted by the Downtown Seattle Association. Downtown hotel occupancy in the March-to-May stretch averaged 84% of 2019 levels.

“The leisure comeback has been stronger than I think a lot of us would have projected,” says Craig Schafer, whose two downtown hotels, Inn at the Market and Hotel Andra, are at around 80% and 70% occupancy, respectively, for May. After a slow January and February due to omicron, he says, “March just took off.”

“We’ve heard a lot about Seattle and we wanted to see it for ourselves,” said Shirley Ellis, an Ohio resident who was at Pike Place Market last week with her family.

They’re not alone, apparently. Seattle is the second most popular domestic destination for Memorial Day travelers, after Orlando, Florida, according to booking data by AAA.

By contrast, downtown’s offices are getting a lot less love this spring.

Although parts of downtown have seen a modest office renaissance — at lunchtime on certain days, the streets around the Amazon spheres at Seventh Avenue and Lenora Street are thronged with badged workers — the overall office worker presence is a still shadow of its pre-COVID self.

Since late February, downtown office occupancy has stalled at around 33%, according to Placer estimates, and that’s despite efforts by many employers to lure workers back with everything from hybrid schedules to free food.

Some observers say it’s even lower. David Gurry, a senior vice president at commercial real estate agency Colliers, who covers downtown office properties, says office occupancy “on any given day is about 22% right now.”

Those estimates are probably missing some returnees. The Placer numbers, for example, only count people in the office three or more days a week. But they do track with low office occupancy rates in several other U.S. cities, including San Francisco and San Jose, California, both of which were at 33.4% as of May 18, according to Kastle Systems, a security firm that measures office occupancy by employees’ key card usage. They also echo national office occupancy rates, which have hovered around 43% since March, Kastle data shows.

“Everybody’s trying to figure out, ‘What can I do to get my people back in the office?’” says Gurry. “And I can tell you that buying everybody lunch doesn’t cut it.”

Two different economies

To some degree, the split-screen recovery between tourism/leisure and the office economy reflects the very different drivers behind these two sectors.

The most obvious difference: Tourism and leisure are pursued for pleasure rather than necessity, which may explain why they’ve been fairly quick to pop back up whenever COVID restrictions are eased or case counts fall.

Consider: While national office occupancy is 43%, attendance at NBA games is back to 95% of 2019 levels and the volume of passengers at airport security checkpoints is at 89%, Kastle data shows. (Passenger volume at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport is at 84% of 2019 levels, according to Port of Seattle statistics; Seattle doesn’t have an NBA team.)

Another big difference: downtown tourism and leisure are benefiting from pent-up demand by consumers who postponed activities in 2020 and 2021. “We didn’t go anywhere for, like, two years,” says Denver resident Chad Chisholm, who was visiting Pike Place Market last week.

The impulse to make up for lost time shows up across the board downtown. As of May 22, roughly 155,000 cruise ship passengers had come through Seattle this season, up 50% over the same period in 2019, despite a COVID outbreak, according to Port of Seattle statistics.

Theaters, nightclubs and other venues, some of the hardest-hit businesses in the city, are also benefiting from consumers catching up.

In January, the 5th Avenue Theatre’s first show in two years, “Beauty and the Beast,” drew 15,000 attendees a week, more than 2018’s popular “Mamma Mia!” The first performances of “Beauty” were “very emotional for the audiences and for the artists,” says Bernie Griffin, the theater’s managing director.

And, paradoxically, many of the workers who don’t want to be back in the office seem OK resuming business travel and conventions. The Seattle Convention Center, which lost most of its bookings in 2020 and 2021 due to COVID, will be back to roughly 70% of its pre-pandemic numbers in 2022.

All those returning business and leisure travelers have brought a much-needed boost for many downtown businesses. Downtown hotels, for example, are seeing those higher occupancy rates without having to cut prices like they did in 2020 and 2021. In April, the average downtown room rate was $195, up nearly 60% from a year ago and roughly even with April 2019, according to Visit Seattle, a trade group.

Although visitor-dependent businesses know those gains could vanish with another COVID wave, they’re “very cautiously optimistic” about 2022 and “bullish about summer in particular,” says Visit Seattle’s John Boesche. “It’s going to feel a lot like a pre-pandemic summer.”

But tourists aren’t enough

Still, even if downtown tourism were to fully recover this summer, that won’t begin to compensate for the loss of office workers, whose lengthening absence creates more uncertainty by month across the entire downtown economy.

Many office landlords and developers aren’t sure what to expect from a downtown market with a 20% vacancy rate as of March, up from 11.4% in March 2020, according to Colliers.

Many employers with expiring office leases “don’t know what they need long term,” says Colliers’ Gurry. Prospective clients may ask to tour 50,000-square-foot spaces one day “and then a week later, they want to come tour 20,000-foot options,” he adds.

Likewise, restaurants and shops that once counted on office workers at lunch or after work have no idea when, or whether, to staff back up or return to a full schedule. That means even fewer workers coming downtown, which affects still other businesses, and further reduces the downtown workforce, which numbered 348,000 before the pandemic, according to Downtown Seattle Association estimates.

Many transit stops that used to see lots of commuters aren’t as busy. At the northbound stop at South Jackson Street and Fourth Avenue South, boardings and exits on King County Metro buses this spring are just 37% of levels in fall 2019. At Third Avenue and Pine Street, they were just 48% of 2019 levels in late March, shortly before the stop was closed following several shootings.

Those lower numbers may also reflect commuters’ safety concerns in parts of downtown. But other areas also saw declines. April ridership into downtown from Snohomish County via Community Transit, for example, was just 23% of April 2019 levels.

Office workers “have considerable leverage”

Some employers cite safety concerns as a key reason downtown workers don’t want to come back. But another reason is that COVID has undercut the case for being in an office at all.

If the pandemic reminded tourists that things like Pike Place Market and the Space Needle are best experienced in real life, it also showed “a good slice of the American labor force, as well as the people who manage them, that work can be … a digital experience,” says Margaret O’Mara, a University of Washington historian who has written extensively about tech hubs like Seattle.

That discovery, coupled with the tight labor market, has given remote office workers leverage over their employers that could last long past COVID, some business experts and employers say.

Eric Johnson, CEO of Nintex, a Bellevue-based process automation company that often competes for talent with Seattle tech firms, says many of those firms have had to relax their return plans to avoid losing workers. Employers “who might want more people to come back have been a little reticent to really push it,” he says.

Some other observers think that leverage will fade if a recession comes and the job market cools.

If employers start to rein in hiring or look for ways to cut costs, any attrition caused by a return-to-office mandate might come to be seen as “an approach to right-sizing head count,” Gurry says.

Others aren’t so sure. Labor demand is so high in the Seattle area, particularly in the very large office-based tech sector, that workers’ leverage “may not significantly change even if we do have a recession,” says James McCafferty, director at the Center for Economic and Business Research at Western Washington University.

That may be a conservative scenario, but it’s one many downtown businesses seem to be planning for.

Back at Pure Food, Hollenbeck and Behar say they aren’t counting on a return of office workers.

“There’s a lot of people that are going to be permanently work from home,” says Hollenbeck. “We’ve kind of adjusted our business plan.”