News

An Urbanist vision for Seattle’s Third Avenue

Posted on

This story was originally published by The Urbanist on Oct. 14, 2022.

Third Avenue in downtown Seattle is a place where many a plan goes to die, and yet the planning efforts keep stacking up. The Seattle City Council recently recommitted to taking another look at how to redesign the street, but the specifics are still being ironed out.

A 2019 study by the Downtown Seattle Association (DSA) continues to be the foundation for that work, as Ryan Packer noted in our recent update on plans. However, visions to revitalize Third Avenue presented by business leaders often go beyond simple urban design tweaks and into calls for fixes to eradicate crime and homelessness — if not citywide, at least to push those problems out of this busy downtown corridor. From this crowd, there also seems to be a desire to upscale the street, attract high-end retail, and part ways with the likes of Ross Dress For Less and McDonald’s.

At The Urbanist, we believe the Third Avenue plan must focus on improving transit service and pedestrian safety. Some sections have great opportunities for street art, pocket parks, and sidewalk cafes. If we make the street more walkable and the bus stops pleasant, safe, and busy, then street life will follow. But the plan should also recognize and promote the unique strengths and needs along each of the distinct sections of the street: Belltown, the Market, the Central Business District, and Pioneer Square.

Prioritize transit service and pedestrian safety

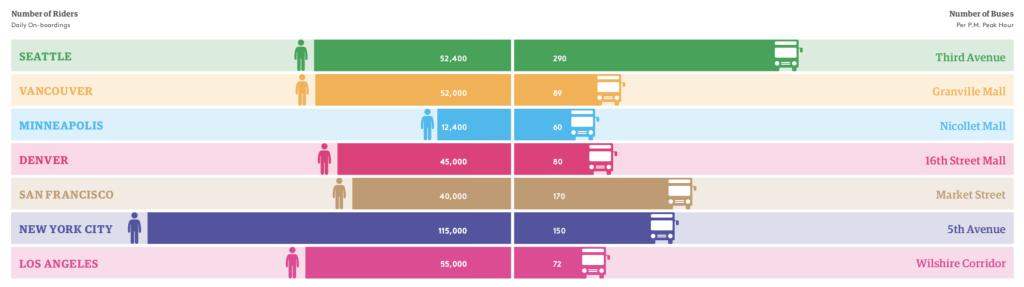

From a numbers standpoint, Third Avenue is one of the most successful transit corridors in the country. Prior to the pandemic, Third Avenue led the nation with 270 buses per peak hour and was also near the top for ridership at around 52,000 bus passengers per weekday. The street consolidates most Seattle bus routes into one corridor that ensures ease of transfers and creates a system that’s easy for visitors to the city to understand.

Thanks to bus-only restrictions, the primary congestion on most of Third Avenue is caused by transit, rather than also having a slew of single-occupant vehicles slowing down bus service. Transit advocates, including The Urbanist and the broader Move All Seattle Sustainably Coalition, long pushed for transit-only restrictions on Third Avenue, and finally succeeded in getting them extended to Stewart Street, although the campaign for bus lanes all the way to Uptown continues.

Maintaining Third Avenue’s usefulness as the city’s foremost transit artery remains a top concern for urbanists. Promoting transit ridership in the post-pandemic era may look a bit different than it did in the past, but Third Avenue will continue to be central to the transit network. As such, DSA’s potential concept of pivoting to transit hubs and a shuttle alternative should be discarded, as it would surely delay and deter riders by forcing transfers at either end of Downtown.

Invest in real solutions for people in mental health and substance abuse crisis

Bus ridership suffered during the pandemic and has been slow to recover. One big reason for the ridership dip is the big jump in work-from-home measures. As of August, only 44% of workers had returned to downtown offices, the DSA reports. Fewer jobs Downtown means fewer peak transit trips. Service cuts that are decreasing frequencies aren’t helping either. But crime and public safety concerns, particularly those focused on Third Avenue, also appear to be sapping transit demand.

Mental health issues spiked during the pandemic, as did an opioid crisis supercharged on fentanyl. Those issues have grabbed the attention of former governor Chris Gregoire, who is CEO of Challenge Seattle, an alliance composed of CEOs from 21 of the region’s largest employers.

“We cannot have an open drug market on Third Avenue and expect we’re going to attract tourists and we’re going to get people to come back to work,” Gregoire said at a recent Grow Seattle event hosted by the Puget Sound Business Journal. Newly appointed SDOT Director Greg Spotts echoed Gregoire’s sentiments just this month when he referenced problems with Third Avenue as central to Seattle’s problems with transit ridership to the national gathering of the American Public Transit Association, calling Third the “center of the fentanyl crisis” in the city.

Drugs have been sold on Third Avenue corners for perhaps as long as there’s been a Seattle, but the idea that we can stamp out this “open air drug market” continues to capture the centrist imagination periodically — and the rhetoric seems to get dialed up during election season. Nobody wants Third Avenue to look like a late-stage Fyre Festival. But if hotspot policing was going to work to permanently move the dealers and junkies off this real estate, it would have worked one of the last half dozen times it was tried in Seattle history.

Even if we did want to go all in on hotspot policing, we couldn’t because of the Seattle Police Department’s capacity constraints. The beleaguered department lost so many officers to retirements and lateral hires during the pandemic that it will take several years to restore them even in the most optimistic scenario using lateral hire incentives and maxing out recruiting classes to fill the ranks. Throwing cops at problems is difficult with such limited resources, particularly since crime issues have spiked in many parts of the city, not just in Downtown hotspots. There’s also the issue of waning efficiency; decreasing clearance rates means the same amount of cops will solve fewer crimes, and the impact of each additional officer is lessened.

Since fixing Third Avenue’s problems can’t ride on policing, King County’s recent plan to levy funds to boost mental health spending and add five new crisis centers is a welcome one. Third Avenue has long hosted “open-air” drug dealing, but it hasn’t always been an open-air mental health institution. It’s crucial we get people living with mental illness the care they need.

The prevalence of people in the throes of mental health crises or drug-addled comedowns has discouraged people from frequenting Third Avenue and the transit along it. We have to take these concerns seriously, while recognizing there are no silver bullets. To fully solve this issue is going to take repairing our frayed social safety net when it comes to mental health, substance use disorder treatment, and supportive housing. Passing the County levy is a start, but making real progress is going to take concerted investment on multiple levels over a sustained period of time.

Use street design to boost the corridor’s strengths

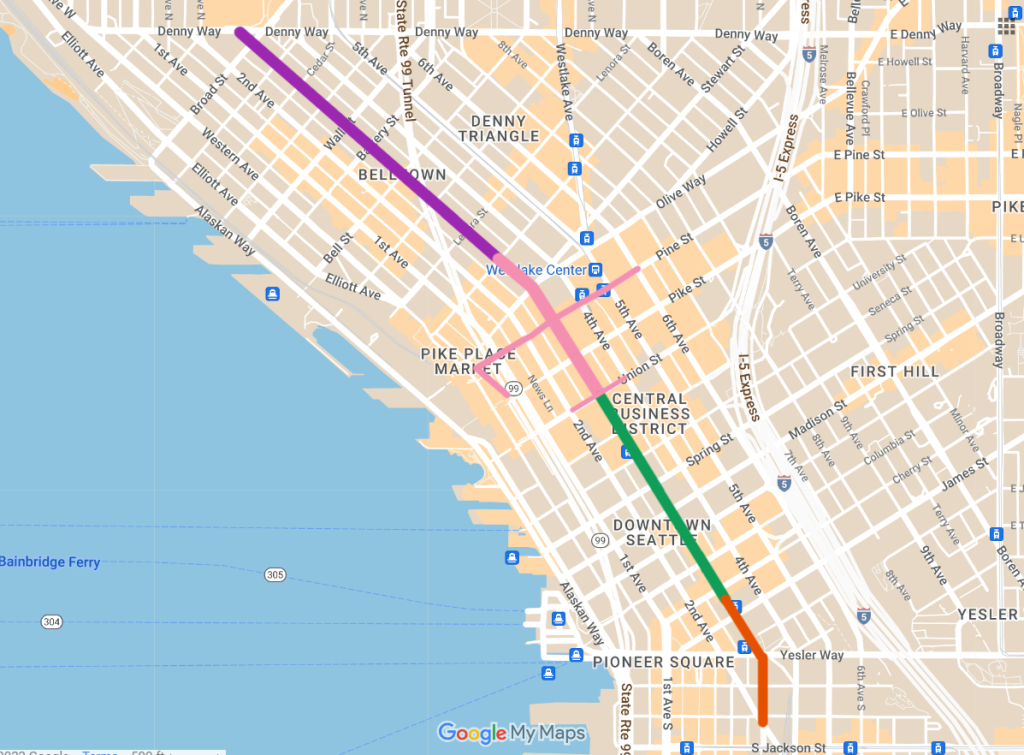

When it comes to street design, Third Avenue could use some improvements, too. Third Avenue has four distinct sections, and each of them demand something different in terms of design tweaks.

First, there’s the Belltown section, which is the most residential in character and also hosts a bustling nightlife district. Apartment towers keep going up in Belltown, which suggests opportunities for the neighborhood to add a grocery store and delis, cafes, and lunch spots, preferably with streateries. It’d be wise to add street trees to this area to make walking more pleasant and encourage people to use the street cafes.

Next up is the Market section which extends from Virginia Street to Union Street. Here’s where more focus could be placed on the side streets. Why not pedestrianize some of the side streets and add programming so that activity spills onto Third? For example, outdoor concerts alongside Benaroya Hall could bring music to the masses, and Pine Street used to be pedestrianized, so we’re not actually proposing anything new here. Pike/Pine is the city’s premier retail corridor. In many leading cities, whether in Europe, East Asia, or Latin America, this corridor would have been pedestrianized decades ago, allowing market stalls and seating to spill into the street alongside happier pedestrians, more apt to linger than flee from speeding motorists.

The third section is the Central Business District (CBD), which is roughly from Union down to Cherry Street. In the CBD, buses land at the foot of some of the city’s tallest office towers. This area will benefit most from returning employees, but the City should not sit idly by waiting for that to happen. Blank walls need to be activated and broken up with murals or art installations. Few dead spaces loom larger than ones created by the downtown post office on the Union Street block opposite Benaroya Hall, although the Bon Marché building parking garage also makes a case. Some light and color on these drab concrete walls could go a long way.

Finally, Pioneer Square is Third’s southernmost section from Cherry to Jackson Street, and repairing the roadway itself to provide a less bumpy ride for bus riders is one need that jumps out. The issue of homelessness and safety is also front and center here. For decades, government has focused social services for an entire county close together near Third and James and then essentially stepped away, leaving the area to become a hub of emergency responses and a symbol of the region’s inadequate response to homelessness, which has stubbornly climbed despite all the campaigns against it.

In addition to better funding homelessness services and supportive housing, the future of City Hall Park and nearby Prefontaine Place will be key to turning around this section of the street. The recent announcement that the City of Seattle will be maintaining ownership of these public spaces means that discussions over whether or not they are Seattle’s or King County’s responsibility can come to end. Now the city government will need to engage with neighborhood stakeholders like the Alliance for Pioneer Square, Chief Seattle Club, and Downtown Emergency Services Center (DESC) to create, and implement, a positive vision for the space. These could be great little parks welcoming folks into Pioneer Square if we solved these issues.

Looking at the big picture

Policymakers must acknowledge that Third Avenue is going to continue to be a transit workhorse, but it can be walkable and loaded with street activation, too. It doesn’t take truncating or weakening bus service to do it. The whole Third Avenue corridor could benefit from bus stop modernization, with functional real-time arrival displays, improved bus shelters, and public WiFi. Seattle could dust off the 2018 transit shelter modernization plan that then-Mayor Durkan shelved. That plan promised not just to pay for itself via the advertising deal, but also to raise nearly $100 million in revenue, which could then fund further improvements.

Third Avenue rightly deserves the focus it’s getting from media and business leaders. But what we need isn’t another big dreamy visioning exercise that goes nowhere or settles on a small incremental change. There are actions and investments that could be made that would produce real results. From regional transit riders, to downtown service workers, there are people from so many different walks of life who pass through this vital corridor on regular basis, and they deserve feel safe and comfortable while walking, riding, biking, or simply spending time there. Third Avenue deserves more than a rebranding exercise or its political football treatment. It’s time to stop dithering and finally commit to investing in one of Seattle’s greatest transit assets.